In the fall I had the opportunity to visit Duke Kunshan University in Kunshan, China for a conference on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—a major foreign investment plan by the Chinese government intended to connect Asia and increase trade and economic growth in the region. The conference—officially titled the “Duke-DKU International Symposium on Environmentally and Socially Responsible Outbound Foreign Direct Investment”—brought together representatives from the Chinese national planning commission as well as academics from China, Southeast and Central Asia, Europe and the United States. It was an amazing opportunity for me to learn a lot about China’s foreign direct investment as well as give a brief presentation about the potential land-use implications of the Belt and Road’s infrastructure.

![Image credit: Lommes [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/img/One-belt-one-road-l.jpg)

Belt and Road Initiative Map

Image credit: Lommes [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Some background: The Belt and Road Initiative is a label used by President Xi Jinping to package a strategy of infrastructure investment intended to increase economic connectivity in Asia. In practice it’s less a literal road than a broad strategy of increased lending for infrastructure with the ultimate goal of creating the economic corridors depicted in the image above. The financing comes via state banks and multilateral institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank, and comes with the expectation of building contracts fulfilled by Chinese state-owned enterprises.

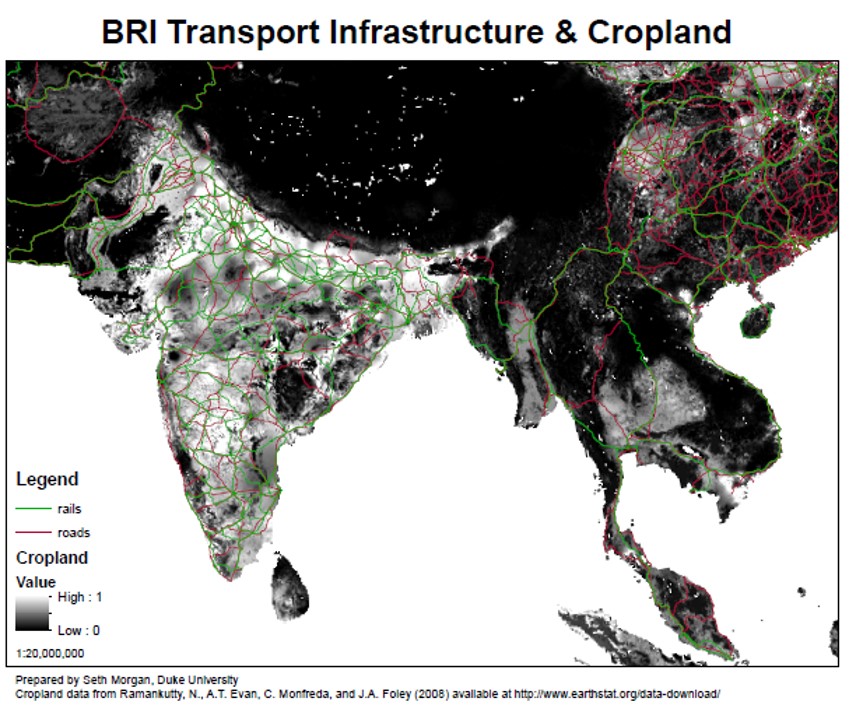

This initiative—though admittedly amorphous and still largely unfulfilled—has the potential to be one of the largest expansions of transportation infrastructure in the world’s history. The land corridors (i.e. the “belt” of the title) across Central Asia, Pakistan and down through Southeast Asia have the potential to increase trade and open up regions, like Tajikistan—whose lack of connectivity I experienced during my Fulbright year—which have been relatively economically isolated up to now. So this is a genuinely historic and potentially transformative development. But it comes with real environmental risks.

These environmental risks are the reason The Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions has become interested in examining the Belt and Road Initiative. This also where research done by my advisor, Alex Pfaff comes in. He’s done a lot of work to estimate the forest impacts of new road infrastructure in Latin America. Now with the advent of this massive push to connect Asia we did a bit of work to draw lessons from that literature that may be relevent for the risks posed to forests by the BRI.

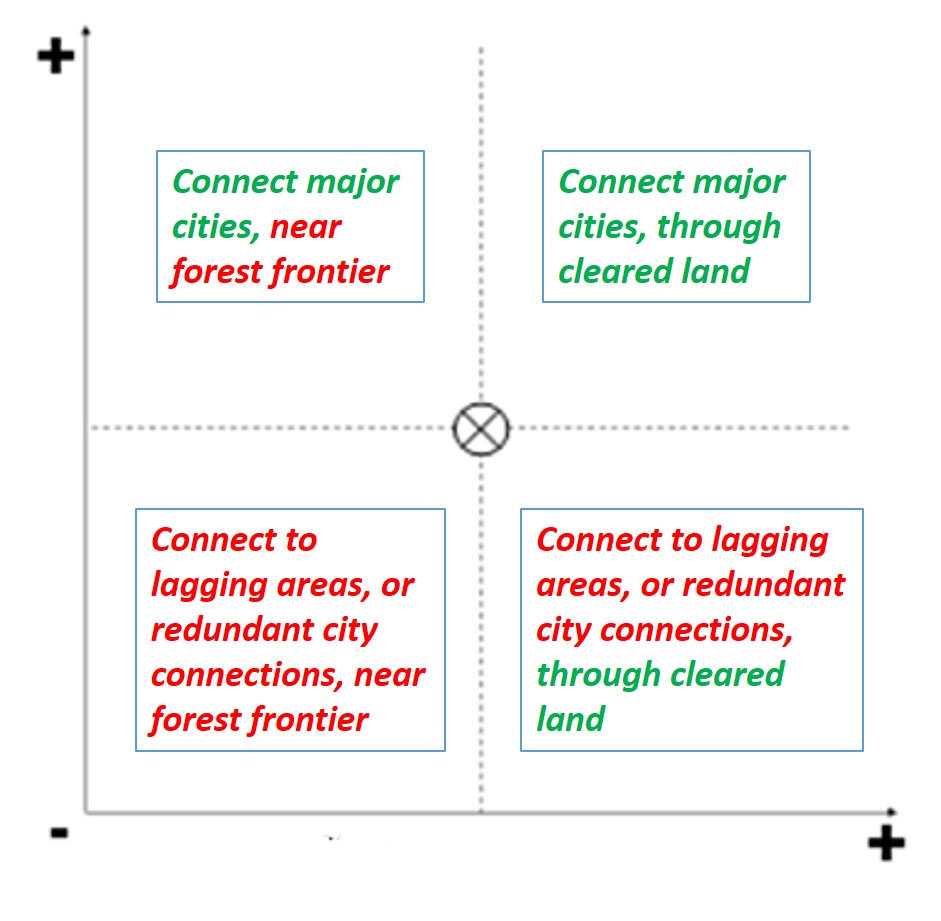

One key takeaway from the literature is that road-building has very different effects depending on where the roads are sited. Alex’s work in Latin American tends to find small deforestation effects in previously cleared agricultural areas and in very remote virgin forest areas, but large clearing effects along the forest frontier, where new roads open up profitable opportunities for clearing farmland and harvesting timber. Moreover, work on roads in India by David Kaczan points to possible net reforestation from roads built through agricultural areas: land use may transition away from extensive agriculture and toward managed forests and tree plantations.

Deforestation Near Roads in Brazil

Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory

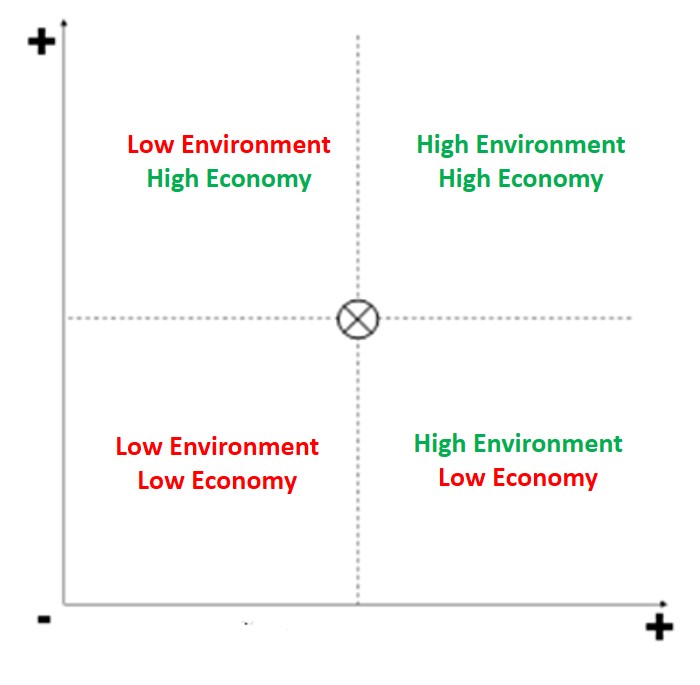

These two insights, that economic growth is best served by connecting economically vibrant cities, and the environment is best protected by avoiding forest frontier areas, led us to present the literature as a set of extremely simplified quadrants.

Agricultural Land Use in South and Southeast Asia

If you want to read more about the Kunshan BRI conference, check out Nicholas student Christine Gerbode’s excellent blog series. And for an on-going take on the politics and economics of the BRI’s implementation give a listen to The Belt and Road Podcast, hosted by Nicholas intern and avid China-watcher Erik Myxter-Iino. I also recommend the World Bank’s page for some great in-depth analysis on the projected economic impacts of the BRI transport corridors.

Many thanks to Yating Li and my other fellow members of Riding the Belt and Road —an interdisciplinary student group at Duke researching the BRI—and to Elizabeth Losos, Lydia Olander and Jackson Ewing at the Nicholas Institute for including us in this conference. It was a remarkable opportunity, and will likely shape my research agenda going forward.