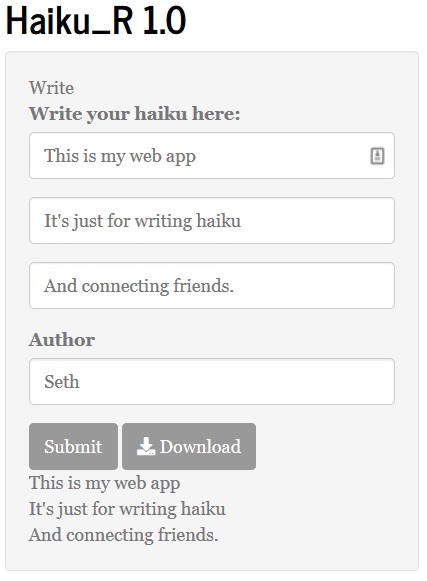

My Haiku App

In 2018, I made a web app for 12 users, all of them family and friends. It did only one thing: collect and display haiku. And it wasn’t very good at it! It was slow and buggy, and it went down unpredictably and stayed down for months at a time because I didn’t have time to maintain it. But it was awesome, and I think you should make one too, even if you—like me—are not even remotely a web developer or software engineer. Why make an app for just your family and friends? Here are a few reasons.

We’re all too far apart

My wife’s family is scattered across two continents and five states. So when they see each other it’s a big deal—and a big expense. The year after we got married we spent Christmas in Kenya, where her parents were based, and instead of exchanging gifts we exchanged haiku. So much cheaper, and more thoughtful! This made me start looking for ways to stay connected year round.

The web is too big

If I want to say something personal or weird, or try out an idea, or make a specific person laugh, I can’t do it on twitter or on my blog. Anybody can read that! The web promised to make the world a more connected place, but what it’s really done is created a big room full of shouting people, with too few social norms to allow for anything like real communication. The more people you have in one room, the more strict the rules need to be. Big ballroom: plenary speaker only, no one else gets to talk. Small conference room: discussion, questions, back-and-forth. Your friend’s living room: stories, jokes, and poetry. Our real lives have different kinds of places for different ways of communicating. So should the web!

Constraints foster creativity

It’s a truism because it’s true. Poetry is formal wordplay. It’s a game humans have been playing for centuries. And it thrives with the right balance of freedom and constraint. Social interactions are similar. Sometimes you need a set of formal constraints to foster good relationships. Right now you could sit down and write an email to anyone you want, and say anything you want. Anything you’re thinking about right now you can send to nearly anyone in milliseconds. But you don’t. You don’t narrate your day to your uncle. Or tell your college friend you miss them. But if someone tells you to write a haiku you might fill that small constrained space with whatever you’re thinking about: your uncle, your friend, your walk in the woods. And you might actually share it. The form’s constraints are like a stage: they say this is where we enact creativity.

Platforms have power

Social media platforms encourage you to share pieces of your life with others, and this can be a good thing. But we’re usually not conscious of the formal constraints and nudges and structure that platforms place on our communication. Building your own app lets you define this structure yourself! Twitter has 280 characters. You get streams of pithy comments and hot takes. Instragram has a photo with a set of tags. You get a gallery of food shots and sunsets. My app has three boxes for the three lines of a haiku. I got a bunch of perfectly compressed slices of life from a dozen people I care about, shared at random times for a whole year. What will you get? It depends on what you make.

Haiku Chapbook Cover

So you want to make a small app? Here are some thoughts on how.

Start with the community

The big web may start with a product then go out and find the users, but it seems to me that small web apps like my haiku-sharing page should start with a well-defined community in mind. Think about who you are connecting, and what they would like to share. Then build something that those ten or twelve or twenty people would like to use.

Use what you have

The appropriate technology community is known for saying “use what you have to make what you need.” I use the statistical language R for my academic work, so I made my app using the R package Shiny, which provides a framework for making interactive web apps where all the coding happens in R. But if you know a bit of Python or Ruby, use that. If you know absolutely zero you might be able to make what you need with WordPress. Or use this as an opportunity to learn a bit of a programming language! Most of all, don’t feel like you have to learn everything. Look up some examples, copy and paste some code, and give things a shot. To check out my (stupid simple) haiku app, take a look at the code on Github. To serve the app I use a virtual machine at Duke, but you can probably host most small web apps using the free tier of AWS. I used these instructions to get my app up and running on an Ubuntu server.

Don’t forget the physical

At the end of one year of sharing haiku, we assembled a chapbook of 2018’s poems. It was so fun to hold a paper object in our hands! And it was a great way to give the experiment a sense of completion. No matter what your small web project happens to be, I think it’s awesome to create something in print as a complement. I used the LaTeX typesetting language to create my chapbook. This Overleaf template for poems, and the booklet package were useful. For the cover image I browsed Unsplash for unlicensed photos, and found the ferris wheel above from photographer Adam Birkett.

I hope my example is encouraging. I really do think nearly anyone can make something cool on the web. I was inspired to think more about digital spaces and the way we interact with books on and off-line by the developer and writer Craig Mod. I recommend his essays and podcast if you want to hear more about what books and apps should be.